More than just numbers: The value of returning birth to Indigenous communities evident in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory

June 15, 2021

The ceremony of birth is being reawakened in First Nations as well as in urban and rural Indigenous communities.

Bringing birth home is the focus of the work of the Indigenous Midwifery team at the Association of Ontario Midwives, the 35 Indigenous midwives and 40 Indigenous students and apprentices within various educational environments across the province.

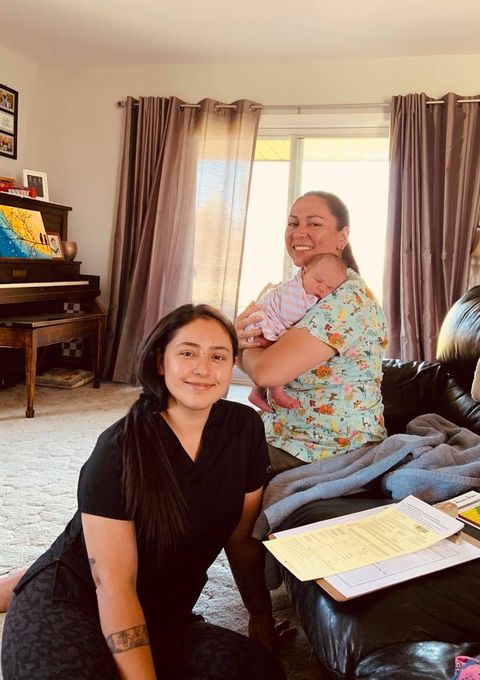

Two midwifery apprentices, Tewahséhtha Brant and Iekonsiio Brant, have been on their midwifery education journey for some time now. Related through marriage, both are members of the Kanyen’kehá:ka nation at Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory. The pair study and provide services to fellow members of their home community as well as to Indigenous clients in local communities through Kenhtè:ke Midwives.

Along with their acquired midwifery skills and knowledge, they are reawakening the cultural understandings and ceremonies that were originally part of pregnancy and birth within their Mohawk community of 2,700. Their vision is to build a birth centre that would serve as a clinic and learning centre within the community. Their intention is to create positive change for all Indigenous families within the territory— enormous goals, though not any different from those of any other community wanting the best for their people.

Tewahséhtha has been an apprentice midwife for more than 10 years. Surprisingly, she is in no hurry to meet the required number of attended births to officially become a midwife. To Tewahséhtha, the needs of her clients are her focus, not the numbers. With her start as a birth doula, followed by an apprenticeship with former preceptor and now-retired Onkwehón:we midwife Dorothy Green, Tewahséhtha jokes that her birth work began as a very expensive hobby. “It’s terrible to put it that way,” she shares, “but that is in fact what we were doing.” She and Dorothy received donated equipment from other Onkwehón:we midwives and their practices. They also paid for their own supplies, gas, food and any other associated costs. Tewahséhtha worked without compensation with the hope that capacity to continue providing such services would be built for the future within the community.

Tewahséhtha recalls the strength and determination of her sister to have a home birth as pivotal to her decision to become a midwife. At the time, there were no midwives providing services in Tyendinaga. To access midwifery care, Tewahséhtha’s sister sold everything she could, packed up and moved in with family whose address fell within the Kingston Midwives’ catchment area. All of these changes were made so that she could birth at home, on her own terms. Witnessing the sacrifices made by her sister, combined with the experience of being a support at the birth of her niece, made such an impression on Tewahséhtha that she too, chose midwifery care during her pregnancy and for the birth of her children. These experiences and the realization that it would be of greater benefit to parents and families to have supports available during pregnancy and birth, rather than just following the birth of their child, helped solidify Tewahséhtha’s decision to become a midwife.

Iekonsiio (Siio for short) came to her apprenticeship after researching birth options while pregnant with her own child. She also sought midwifery services from Dorothy Green, and her interest in midwifery and subsequent studies grew from there. Siio is currently in her third year of apprenticeship. She acknowledges that there has been a significant change with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: “Trying to stay focused on education has been a bit of a struggle personally, because I need to be in it—to feel it, I suppose.” In addition to studying to become a midwife in the midst of a pandemic, Siio is also parenting and building a home for herself and her five-year-old daughter. Still, she finds time for herself, through reading, practicing her art and venturing out on hikes.

Tewahséhtha and her family were returning from ceremonies just as the interview for this story began. Both she and her husband are staunch supporters of the revitalization of the cultural practices and language within their community. Their two daughters, ages 13 and 11, are the first, first-language Mohawk speakers in Tyendinaga in over three generations. An incredible feat, as both Tewahséhtha and her husband, Thohtharátye (Joe) Brant, had to learn the language themselves prior to teaching their children.

These revitalization efforts are carried over into the birth work of both Tewahséhtha and Siio. Among the understandings of the Onkwehón:we people are that leather should be placed on the wrist of the newborn for protection and connection to the Earth, and that the first sounds that a newborn hears are to be their ancestors’ language. This requires a fluent Mohawk language speaker to be present at the birth of those in the care of Kenhtè:ke Midwives.

The ability to provide wholistic care and meet the cultural and language needs of both the parent and the newborn within local health-care settings have not come without enormous challenges and struggles. Care providers within these institutions would not have understood the needs of Indigenous clients without the education and advocacy efforts of the team at Kenhtè:ke Midwives.

These efforts, as well as other health-care providers being witness to the care provided by the team at Kenhtè:ke Midwives, helped bring about many beneficial changes that support the wholistic needs of Indigenous clients. Incredibly, Kenhtè:ke clients now have two support people in the operating room: one person to care for and support the parent and one to care for and support the infant. The needs of the clients are the priority, rather than what is convenient for the care provider, such as choice of birthing position and the removal of unnecessary monitoring. Placentas are returned to the parent upon request. Kenhtè:ke Midwives’ demonstration of care has been so profound, they have gained many supporters and advocates within the local health-care system.

Even with these supports, barriers continue to exist for Onkwehón:we midwives working under the Exemption Clause of the Midwifery Act (1991). Some of these barriers include the fact that Aboriginal Midwives (AMs) working under the Exemption Clause still do not have the provincial billing numbers required to order lab tests and ultrasounds and, at times, are seen as ‘less than’ by some of their colleagues within the health-care system and even community. Because AMs cannot hold hospital privileges, they must transfer care of a labouring client to a physician or Registered Midwife on arrival and assume a supportive role for the birth. This excludes births that take place in a hospital from being counted towards fulfillment of an apprentice midwife's requirements, regardless of how much labour care they provided under their preceptor's supervision outside of the hospital. The lack of billing numbers means AMs working under the Exemption Clause are forced to find alternative ways to obtain tests and results, a critical impediment to the provision of safe, timely care to one of the most at-risk populations in the country. At best, AMs are forced to rely on partnerships with allied health professionals who are able to order and access test results for them. At worst, the delay in obtaining testing and results can have detrimental impacts on the expected outcome of a birth.

Convincing the community that they have the knowledge and skills to deliver safe midwifery care in the territory takes fortitude, perseverance and a belief in themselves and their work. Tewahséhtha and Siio have these qualities. Their commitment to continually battling the system to make services more culturally safe for their clients and the community of Tyendinaga speaks volumes. Their numbers are growing as well; they currently have 23 clients on their roster and it’s only the second quarter. By comparison, there were 26 clients in total in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic has driven a significant increase in client load, an impact which has also been felt in other Indigenous Midwifery Programs reporting a 50% increase in the demand for services over the past year. Though working through the pandemic poses many additional challenges, it may also be seen as a blessing in disguise. The pandemic has given these apprentices time to learn, develop their skills and embed their care even deeper within the community.

Julie Wilson, Supervisor of Tsi Non:we Ionnakeratstha Ona:grahsta' / Six Nations Birth Centre and former Registered Midwife, is midwifery preceptor for Siio and Tewahséhtha.

“Tewahséhtha, she really loves her clients,” Julie shares. “She really cares for and loves her community. It doesn’t matter where they end up birthing; it’s important for her that she provides the same care. So, that really speaks to your dedication and your commitment to the community as opposed to commitment to self [and the numbers].

Siio is a younger midwife. She’s very mature and you can tell that this was her gift…. It’s nice to see that she, despite her young age, that she has that respect; respect among the community.”

Julie and her team at the birth centre have been providing midwifery care within the Six Nations of the Grand River community since 1996 and have been providing midwifery education for almost as long. Their training and education not only meet the requirements of the College of Midwives of Ontario but, more importantly, follow the original ways of the Onkwehón:we people and the needs and wishes of their clients.

“I think that Indigenous midwifery really is about caring for and love for the community,” Julie explains. “We have a duty to provide and care for our people. We’re part of that community. It’s not just an individual profession, meaning, ‘I’m going to do this and I want to start doing this practice in this way or I want to practice here.’ It’s not like that; it’s something that you do to serve. It’s a lot of sacrifices. I see Indigenous midwifery as a way of promoting a healthy community, through midwifery. But our ultimate goal is to promote community wellness and healing. So, midwifery is one of the best ways of doing that. I do believe it’s the best model…. Taking care of our own really is important and birth is one of the most beautiful traditions. It’s our ceremony, one of our most important ceremonies. It’s amazing work, it’s healing—there are so many profound benefits.”

By bringing the ceremony of birth back to community, Indigenous midwives like Julie and their apprentices such as Tewahséhtha and Siio are mending the circle broken by the colonial system and the medicalization of birth. The circle will be complete when the beauty, joy and ceremony of birth is returned to all Indigenous communities here on Turtle Island. Together, Julie, Tewahséhtha and Siio are part of the movement toward the reawakening of Indigenous midwifery and the promise of new life.